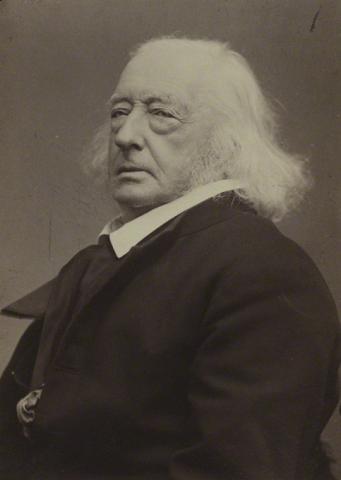

SOME OF

THE MOST BEAUTIFUL POEMS

INSPIRED BY

THE ETERNAL MESSAGE OF GREECE

JOHN STUARD BLACKIE

1880

LAYS AND LEGENDS

PROMETHEUS

No character of primeval Greek tradition has been a greater favourite with modern poets than the hero of the well-known play of Aeschylus. The common conception of him, however, made fashionable by Shelley and Byron, as the representative of freedom in contest with despotism, is quite modern; and Goethe is nearer the depth of the old myth, when, in his beautiful lyric, he represents the Titan as the impersonation of that indefatigable endurance in man which conquers the earth by skilful labour, in opposition to and in despite of those terrible influences of the wild elemental powers of Nature, which, to the Greek imagination, were concentrated the person of Jove. On the apparent impiety of the position of Prometheus, as against the Olympian, see my ‘Horae Hellenicae’.

P©saj tšcnaj broto‹sin ™k Promeqšwj. –Aeschylus

I.

Blow blustering winds; loud thunders roll!

Swift lightnings rend the fervid pole

With frequent flash! His hurtling hail

Let Jove down-fling! Hoarse Neptune flail

The stubborn rock, and give free reins

To his dark steeds with foamy manes

That paw the strand! – such wrathful fray

Touches not me, who, even as they,

Immortal tread this lowly sod

Born of the gods a god.

II.

Jove rules above; Fate willed it so.

‘Tis well; Prometheus rules below.

Their gusty game let wild winds play,

And clouds on clouds in thick array

Muster dark armies in the sky;

Be mine a harsher trade to ply,

This solid Earth, this rocky frame

To mould, to conquer,

and to tame;

And to achieve the toilsome plan,

My workman shall be MAN.

III.

The Earth is young. Even with these eyes

I saw the molten mountains rise

From out the seething deep, while Earth

Shook at the portent of their birth.

I saw from out the primal mud

The reptiles crawl of dull cold blood,

While winged lizards with broad stare

Peered through the raw and misty air.

Where then was Cretan Jove? When then

This king of gods and men?

IV.

When naked from his mother Earth,

Weak and defenceless, man crept forth,

And on mis-tempered solitude

Of unploughed field and unclipt wood jsk

Gazed rudely; when with brutes he fed

On acorns , and his stony bed

In dark unwholesome caverns found;

No skill was then to till the ground,

No help came then from his above,

This tyrannous-blustering Jove.

V.

The Earth is young. Her latest birth,

This weakling man, my craft shall girth

With cunning strength. Him I will take,

And in stern arts my scholar make.

This smoking reed, in which I hold

The empyrean spark, shall mould

Rock and hard steel to use of man;

He shall be as a god to plan

And forge all things to his desire

By alchemy of fire.

VI.

These jagged cliffs that flout the air,

Harsh granite blocks so rudely bare,

Wise Vulcan’s art and mine shall own,

To piles of shapeliest beauty grown.

The steam that snorts vain strength away

Shall serve the workman’s curious sway

Like a wise child; as clouds that sail

White winged before the summer gale,

The smoking chariot o’er the land

Shall roll, at his command.

VII.

Blow , winds, and crack your cheeks! My home

Stands firm beneath Jove’s thundering dome,

This stable Earth. Here let me work!

The busy

THE NAMING OF ATHENS

The beautiful and significant local myth embodied in this ballad conveys a grand lesson in political economy to all nations who, in the pursuit of wealth by manufactures, commerce, or otherwise, may be tempted to neglect the fundamental interests of landed property, and the rights of the honest food-producing labourers who till the soil. It were well for modern Greece, at the present hour, if it could be brought to understand, and practically to strive after, the realisation of this great principle. A people consisting of mere merchants, without any root in the native soil, can never become a nation. The contest between Pallas and Poseidon was represented on the posterior pediment of the Parthenon. –Pausanias, i. 24, 5. The same struggle between the same adverse deities existed in Troezene, and was wisely compromised. –Pausan., ii. 30, 6. Gerhard remarks that in these contests of local gods with Neptune the sea-god is generally the loser. – ‘Mythol.,’ 633; C. O. Müller, Minerva Pol.,‘ p. 7. To the English people, as the conservators of the Elgin Marbles, the whole subject possesses a peculiar interest.

Parqšnoi ÑmbrofÒroi

œlqwmen lipar¦n cqÒna P£lladoj, eÜandron g©n

Kškropoj ÑyÒmenai polu»maton. – ARISTOPHANES

On the rock of Erectheus the ancient, the hoary,

That rises sublime from the far-stretching plain

Sate Cecrops, the first in Athenian story

Who guided the fierce by the peace-loving rein.

Eastward away by the flowery Hymettus,

Westward where Salamis gleams in the bay,

Northward, beneath the high-peaked Lycabettus,

He numbered the towns that rejoiced in his sway.

Pleased was his eye with the muster, but rested

At length where he sate with an anxious love

When he thought on the strife of the mighty broad-breasted

Poseidon, with Pallas, the daughter of Jove;

For the god of the earth-shaking ocean had sworn it,

The city of Cecrops should own him supreme,

Or the land and the people should ruefully mourn it,

Swamped by the swell of the broad ocean-stream.

Lo! from the north, as he doubtfully ponders,

A light shoots far-streaming; the welkin it fills;

Southward from Parnes bright-bearded it wanders,

Swift as the courier-fires from the hills.

Far on the flood of the winding Cephissus,

There gleams like the shape of a serpentine rod,

Shimmers the tide of the gentle Ilissus

With radiance from Hermes the messenger-god.

’Twas he: on the Earth with light touch he descended,

And struck the grey rock with his gold-gleaming rod,

While Cecrops with low-hushed devotion attended,

And reverent awe to the voice of the god.

“Noble autochthon! A message I bear thee,

From Jove in Olympus who regally sways;

Wise is the god the dark trouble to spare thee, –

Blest is the heart that believes and obeys.

On the peaks of Olympus, the bright snowy-crested,

The gods are assembled in council to-day;

The wrath of Poseidon, the mighty broad-breasted,

’Gainst Pallas, the spear-shaking maid, to allay;

And thus they decree – that Poseidon offended,

And Pallas shall bring forth a gift to the place;

On the hill of Erectheus the strife shall be ended,

When she with her spear, and the god with his mace,

Shall strike to quick rock; and the gods shall deliver

The sentence as Justice shall order; and thou

Shalt see thy loved city established for ever

With Jove for a judge, and the Styx for a vow.”

He spake; and, while Cecrops devoutly was bending,

To worship the knees of the herald of Jove,

Shone from the pole, in full glory descending,

The cloud-car that bore the bright gods from above,

Beautiful, glowing with many-hued splendour.

O what a kinship of godhead was there!

Juno the stately, full-eyed; and the tender

Bland-beaming Venus, so rosily fair;

Dian the huntress, with arrow and quiver,

And airily stripping with light-footed grace;

Apollo, with radiance poured like a river

Diffusive o’er Earth, from his joy-giving face;

Bacchus the rubicund; and with fair tresses,

The bright-fruited Ceres, and Vesta the chaste;

And the god that delights in fair Venus’ caresses,

Stout Mars, in his mail adamantine encased.

Then, while wild thunders innocuous gather

Round his brow, diademed green with the oak,

On the rock of Erectheus descended the Father,

And thus to good Cecrops serenely he spoke:

“Kingly autochthon! The sorrow deep-rooted

that gnaweth thy heart, the Olympians know;

too long with Poseidon hath Pallas disputed,

this day shall be peace, or great Jove is their foe.”

He spake; and a sound like the rushing of ocean,

From smoothed-grained Pentelicus, seizes their ears;

From his home in Euboea, with haughty commotion,

O the place of the judgment, the sea-monarch nears.

On the waves of the wind his blue car travelled proudly,

Proudly his locks to the breezes floated free,

Snorted his mane-tossing coursers, and loudly

Blew from the tortuous conch of the sea

Shrill Tritons the clear-throated blast undisputed,

That curleth the wild wave, and cresteth the main;

While Nereids around him, the fleet foamy-footed,

Floated, as floated his undulant rein.

Thus on the rock of Erectheus alighted

The god of the sea, and the rock with his mace

Smote; for he knew that the gods were invited

To judge of the gift that he gave to the place.

Lo! at the touch of his trident a wonder!

Virtue to Earth from his deity flows:

From the rift of the flinty rock cloven asunder,

A dark-watered fountain ebullient rose.

Inly elastic with airiest lightness

It leapt, till it cheated the eyesight; and, lo!

It showed in the sun, with a various brightness,

The fine-woven hues of the rain-loving bow.

“WATER IS BEST!” cried the mighty broad-breasted

Poseidon; “O Cecrops, I offer to thee

To ride on the back of the steeds foamy-crested,

That toss their wild manes on the huge-heaving sea.

The globe thou shalt mete on the path of the waters,

To thy ships shall the ports of far ocean be free;

The isles of the sea shall be counted thy daughters,

The pearls of the East shall be treasured for thee!”

He spake; and the gods, with a high-sounding paean,

Applauded; but Jove hushed the many-voiced tide;

“For now, with the lord of the briny Aegean,

Athena shall strive for the city,” he cried.

“See, where she comes!” – and she came, like Apollo,

serene with the beauty ripe wisdom confers;

the clear-scanning eye, and the sure hand to follow

the mark of the far-sighted purpose, was hers.

Strong in the mail of her father she standeth,

And firmly she holds the strong spear in her hand;

But the wild hounds of war with calm power she

commandeth,

And fights but to pledge surer peace to the land.

Chastely the blue-eyed approached, and, surveying

The council of wise-judging gods without fear,

The nod of her lofty- throned father obeying,

She struck the grey rock with her nice-tempered

spear.

Lo! from the touch of the virgin a wonder!

Virtue to Earth from her deity flows:

From the rift of the flinty rock cloven asunder,

An olive-tree greenly luxuriant rose –

Green, but yet pale, like an eye-drooping maiden,

Gentle, from full-blooded lustihood far;

No broad-staring hues for rude pride to parade in,

No crimson to blazon the banner of war.

Mutely the gods, with a calm consultation,

Pondered the fountain, and pondered the tree;

And the heart of Poseidon, with high expectation,

Throbbed, till great Jove thus pronounced the decree:

“Son of my father, thou mighty broad-breasted

Poseidon, the doom that I utter is true;

Great is the might of thy waves foamy-crested,

When they beat the white halls of the screaming sea-mew:

Great is the pride of the keel when it danceth,

Laden with wealth, o’er the light-heaving wave;

When the East to the West, gaily floated, advanceth,

With a word from the wise, and a help from the brave.

But Earth, solid Earth, is the home of the mortal,

That toileth to live, and that liveth to toil;

And the green olive-tree twines the wreath of his portal,

Who peacefully wins his sure bread from the soil.”

Thus Jove; and aloft the great council celestial

Rose, and the sea-god rolled back to the sea;

But Athena gave Athens her name, and terrestrial

Joy, from the oil of the green olive-tree.